"The bottlenose dolphins were being exposed to sounds up to 160 dB. That's louder than a 747!"

Well, actually, it's not.

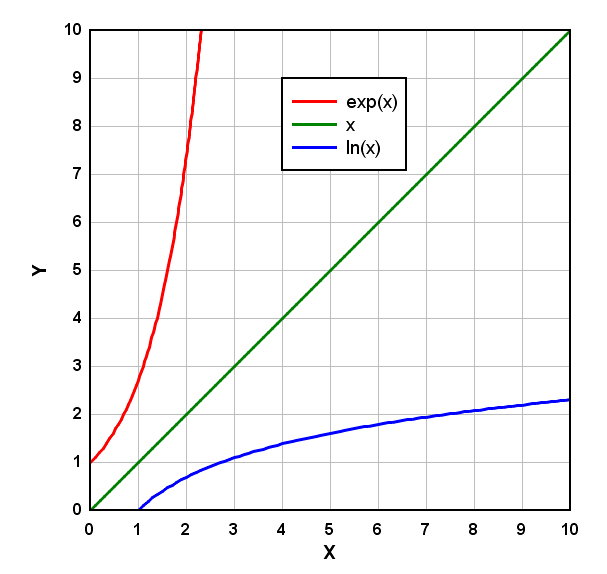

The problem here is related to the units with which we measure sound. First of all, we measure sound using the decibel. Decibels are logarithmic units. Basically, logarithmic scales allow us to make big numbers smaller so that they are easier to visualize. For example, in the chart below, you can see that when we take the log of value for x (in green), the log values (in blue) are decreased more for large values of x than for small values of x. The opposite is true of taking an exponential of x, such as x^2 (in red).

Why make things so complicated when we talk about sound? Well, human beings actually perceive sound pressure in a log scale. For example, you wouldn't really be able to tell the difference in loudness between 6 trumpet players and 7 trumpet players, because your brain doesn't process sound lineally. In fact, every time you want to change the loudness level by just three measly decibels, you have to double the power. So, if you want to increase the loudness of your trumpet players by 3 dB, you'll need 6 more trumpets.

Doublemint gum only makes you 3 dB louder, just ask the dolphins.

OK, so now we understand decibels, why can't we compare dB in air with dB in water?

First of all, decibels must always be referenced to some standard. In air, decibels are referenced to 20 micropascals (pascals are a unit of pressure). In water, they are referenced to 1 micropascal. This means that, from the start, 26 dB must be added to the sound level to make the two references levels the same.

Secondly, water is much denser than air, so the effects of pressure are also different. Although it is possible to compress water, it is much more difficult to do so. In fact, when we add the difference in densities between air and water into the equation, we find that the sound pressure in water is 60 times greater (or 35.6 dB higher) than the same value in air.

|

| Loud, but not as loud as a plane. Photo from the CRRU. |

So, if white-beaked dolphins are producing whistles that are between 139 and 148 dB, that doesn't mean that they are making sounds louder than a 747. If we convert those numbers to values in air, we get somewhere between 103 and 113 dB. Which is still pretty darn loud, but not quite as loud an airplane engine. It's also good to point out that dolphin whistles are "narrowband" sounds. I explained narrowband in an earlier blog post, but basically what this means is that you can't imagine a whistling dolphin sounding like a jackhammer, because the sounds cover a very different range of frequencies and are produced by very different mechanisms.

So, next time you read something comparing underwater sound compared to sound in air, check to see if they did their conversions right!

I recommend reading "Issues relating to the use of a 61.5dB conversion factor when comparing airborne and underwater anthroprogenic noise levels" by Finfer, Leighton and White.

ReplyDeleteGreat post, really interesting blog!

ReplyDelete